The first time I knew that my father had rowed competitively was around my sixth birthday. I was in our kitchen with my mother. High above her head, I saw four or five objects made out of a tarnished metal. What were they?, I asked. “Your father’s cups”, my mother answered. “Haven’t I told you that he was a rower?”

Rowing, when I asked, turned out to mean rather more than the occasional paddling of a dinghy which was a necessary part of my parents’ weekends yachting. At 18, my father had won his school’s senior sculls. He has taken part in the 1948 Henley Regatta in a eight that beat Leander, who a month later won silver for England at the Olympics. He raced for Oxford twice in the Boat Race, at a time when the BBC sent more cameras to film the contest between Light and Dark Blues than it did even to the state opening of Parliament.

My father learned to row at the age of fourteen. His school had a fixed routine for teaching new boys to row. Once a boy could swim 100 metres or so, they would go to a boathouse and be placed in a clinker skiff, and from there they built up slowly to sculling boats with first fixed and then sliding seats.

My father was passed over for the junior eights, and spent his summers sculling by himself. Largely untaught, but enjoying the exercise, he found himself slowly building up his distance until he was rowing dozens of miles every week.

Over time he mastered the technique of rowing. As he has described it to me: “The sculler swings fully forward getting his sculls as far back as he can with his arms flat out forward. The sculls are entered into the water with a flick of the wrist. He must simultaneously push his weight on his legs as quickly as he can. If the entry into the water is slow the boat will be temporarily stopped. Half way through the stroke the rower swings his body back and finally pulls the oars close to the body.”

“Sculling on the Tideway has particular problems because of the floating debris at high tide. When the river is high, waves also rock the boat as they bounce off the tidal walls. This makes balancing the boat very hard.”

A photograph of his house rowing eight, taken two years later, shows my father standing in the back row. The boys show off a collection of trophies, four of which appear to have been won by the junior rowers. My father’s contribution was the sculling cup, as the best solo oarsman in his year.

At seventeen, my father won his school’s junior sculls. Immediately after, he raced in the senior sculls, coming second against boys a year older than him. At one key moment, he found himself in direct competition with a rower in the school’s first eight. My father, to his own astonishment, passed the senior boy without difficulty. He was promoted immediately to the school’s first eight.

My father rowed for Oxford in the 1950 boat race, an occasion overwhelmed by the illness of Oxford’s stroke (the rower who sets the pace), Christopher Davidge, who was struck down by jaundice and had to be replaced just days before the race.

By 10am, the Evening Standard reported, “crowds of Cup Final size were jostling through Hammersmith, Chiswick, Putney and Mortlake.” Oxford chose the Surrey station. They led at the start, and the crews were still level after a mile, but Cambridge drew ahead in the second mile. At Hammersmith Bridge, Oxford had the bend in their favour and reduced Cambridge’s lead.

I imagine my father, already near the very limits of his strength, trying to increase the power of his stroke. He had to find more energy when his body was already near its fastest pace, yet he could not row with too much force for fear of disrupting the other rowers in his own boat.

Oxford increased their pace to a punishing 34 strokes per minute, Cambridge however had the benefit of the bend at the Middlesex station. Cambridge were ahead, but erratic steering by their cox brought them close to the Oxford boat, and for a brief moment the two crews’ oars touched before separating again.

As the river straightened, Cambridge remained in the lead and Oxford could not wear their rivals down. Slowly, Cambridge’s lead mounted. They eventually rowed out winners by the comfortable margin of three-and-a-half lengths.

In summer 1950, my father won the Oxford Sculls and Pairs and the Senior Sculls at Henley. In the Oxford sculls, he beat Tony Fox, who would later represent Britain in the 1952 and 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

He put himself forward again for the 1951 race. Oxford had every reason to believe they would get their revenge on Cambridge. Davidge was well and returned to his rightful place as Oxford’s stroke. My father was one of several members of the Oxford crew to benefit from the experience of having raced the year before.

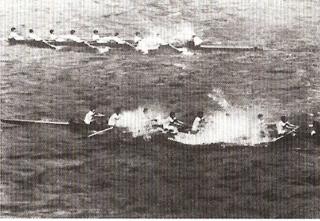

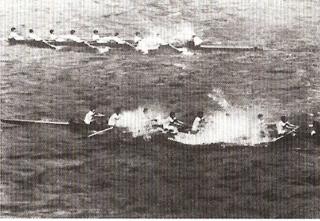

As the crews approached the stake boats, they hit a brief squall. The water was now very rough, and both boats found themselves low, having taken on water.

On the BBC launch were John Snagge and the former Oxford and Cambridge blues Jock Clapperton and Ronnie Symonds. It was Clapperton who described the start: “There is no doubt about it, Cambridge did go away beautifully in the very, very rough water … They are nearly four lengths ahead … I have never seen in many, many Boat Races a crew go away as quickly as Cambridge have. Oxford have in their start made very, very heavy weather of it, much more so than Cambridge. They are not together and it looks to me as though they are shipping an enormous amount of water. It will surprise me if they are able to keep going at this rate much longer.”

Oxford sank; and when the race was re-run, they went down to a second humiliating 12-length defeat, in the most one-sided boat race in five decades,

There was a particular prize to that year’s boat race. The winners of the race had been invited to America where they were to race against Yale and Harvard. Cambridge’s subsequently victories in that competition were widely reported in the press; and the triumphant college oarsmen were presented to His Majesty King George VI. Later that year, racing on behalf of Great Britain in the European championships, Cambridge won the gold medal. They were national heroes.

The defeat took place just one day after my father twenty-first birthday. He did not ask to be considered for the following year’s race. Over the next fortnight, he converted to Roman Catholicism, a decision he had long been pondering.

Some of the Oxford crew returned in 1952; when they beat Cambridge. But for those who did not, rowing ended abruptly and in humiliating circumstances. My father was a strong and proud man. I was just four when Cambridge sank in the 1978 boat race; and I remember the sadness on my father’s face when the BBC brought out the old archive images of Oxford’s 1951 defeat.

Here’s the youtube clip of the 1951 debacle:

http://youtu.be/-fibmgnPNpk